Author and writing coach Larry Brooks introduced me to a writing tool called a “beat sheet.” It has become my favorite story planning tool. Put simply, a beat sheet is an ordered list of the scenes in your book; an outline, more or less. The name comes from a drumming analogy, where the story milestones in your book are the “beats” of your story.

A beat sheet gives you a way to see the “big picture” of your story. Larry describes them on his blog at storyfix.com and in his book Story Engineering (see bibliography below for links). This article explains how I put one to work on my first novel, Vaetra Unveiled.

A beat sheet is a great tool for story planning before you even start writing your first draft, but it can come in handy as a post-draft diagnostic tool as well.

Using a Beat Sheet for Story Planning

When I started planning Vaetra Unveiled, I melded two story structure techniques. I started with Randy Ingermanson’s Snowflake Method, which builds a story around “three disasters and an ending.” I fit those plot elements into Larry’s four-part story structure, in which he augments the classic “three act” structure by splitting Act 2 into two “parts.”

I further applied Larry’s story structure techniques from his book and added the following story milestones:

- Opening

- Hook

- First Plot Point (“first disaster”)

- First Pinch Point

- Midpoint (“second disaster”)

- Second Pinch Point

- Second Plot Point (“third disaster”)

- Climax/Resolution

In case you are wondering, a “pinch point” is a place where the opposition (or villain) makes a move or otherwise rears up into the foreground of the story.

The cool thing about a beat sheet is that it does not have to fully describe the entire story, although you could use it that way and effectively have a complete outline of scenes before you begin writing.

You can use just about any method you want to create your beat sheet, including a pen and paper. I used Excel because it is easy to insert, move, and delete rows. You can also easily add new columns of information.

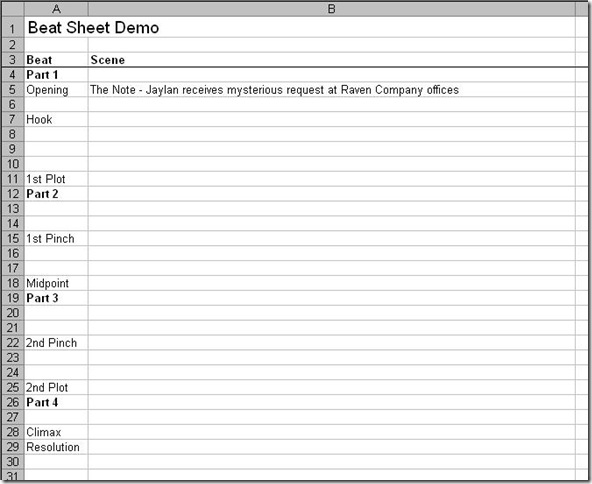

Starting simple, your beat sheet might have just two columns: one for the scene description and one for a label that identifies the story milestone reached in that scene. In fact, your beat sheet might start with nothing but milestone placeholders. You can fill in scenes as you come up with ideas for them, or even as you start writing the story.

I describe scenes by giving them a short name that would remind me what they were about, and I added a description that explains what the scene accomplishes in the story. For example, I described my first scene this way (Jaylan is my main character’s name):

The Note – Jaylan receives mysterious request at Raven Company offices

Here’s an example of how a simple beat sheet might start (click image to expand):

The example shows only thirty scenes, and your book will probably have more than that, but that’s fine. Just insert new rows as you add more scenes. Vaetra Unveiled ended up with sixty scenes.

The goal is to start with a scene description for each of the major beats of your story (opening, hook, etc). If you can do that, writing the rest of the story is much easier. The other scenes form the connective tissue that tie together your major plot points and further develop your characters, your subplots, and your story world.

Nothing says you have to write your scenes in order. A beat sheet allows you to bounce around in the story and write the scene you want to write at that moment, all the while knowing exactly how and where that scene fits into your story.

A beat sheet helps you write faster and avoid major rewriting.

Using a Beat Sheet for Story Diagnostics

You might think that a beat sheet is only useful before you start writing and during the development of your story, but that isn’t necessarily true. If you have already written a story that just doesn’t seem to work, you might try putting the story into a beat sheet for review. It can help you identify what’s missing and what seems out-of-order.

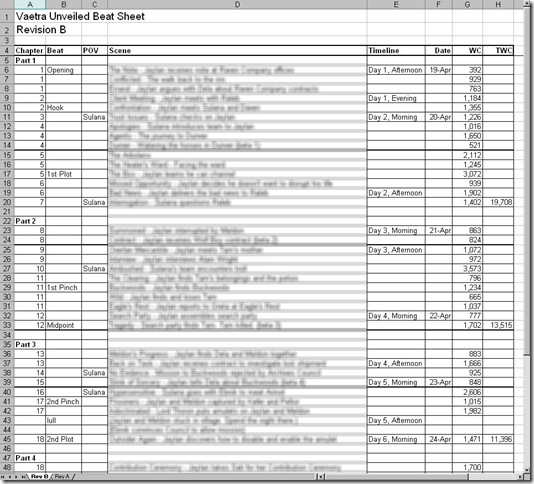

I used my beat sheet for Vaetra Unveiled extensively during my first draft. It evolved several times as I came up with ideas for additional columns with helpful information.

By the time I was done with the first draft, my beat sheet looked like this (click image to expand):

While I was writing, I found it helpful to identify which scenes were written from which point of view, so I added a POV column. (The empty cells indicate that they are in the main character’s point of view.) I also added a Timeline and Date column to help me keep track of which events were happening when within the story timeline. Those columns helped me be consistent with character travel times and with simultaneous events that happened in different locations or points-of-view.

After I finished the first draft, I got ready for my revision pass. I wanted to release the book to beta readers a chunk at a time over the course of seven weeks. To do that, I decided I needed to figure out what scenes would go into which chapters, and which chapters would be part of each beta release. I added a “Chapter” column so I could assign scenes to chapters. The thick lines after some chapters indicate the break points for the beta releases.

I also added the WC (Word Count) and TWC (Total Word Count) columns. While writing the first draft, I didn’t reach my word count goal, so the word counts by scene helped me quickly identify which areas of the story have the most “room” for deeper development. At the same time, it helped me keep the four parts of the story reasonably balanced.

If you are a writer who is struggling with your story or having trouble getting started with one, give a beat sheet a try. You don’t have to go as far as I did with mine, you may find that just having a list of scenes gives you the perspective you need.

And the Pantsers All Screamed

Even other story planning fans may think I’ve gone a little too far here. Organic writers, who prefer to write by the seat of their pants (aka “pantsers”), are probably all outside throwing up right now. They often see story planning and story structure as “formulaic.”

Yes, there is a formula for good story structure. But there’s no formula for a good story. Story structure gives you tangible writing goals and a proven architecture for a story that entertains. It’s up to you to come up with the plot and the characters that take maximum advantage of the underlying framework.

I didn’t feel like my creativity was stifled at all. In fact, I felt like my creativity was liberated when I no longer had to worry about what I needed to write.

Knowing where you are going makes it far easier to relax and enjoy the journey.

Bibliography

Randy Ingermanson’s Snowflake Method

Larry Brooks’ Blog Post on Beat Sheets

Story Engineering by Larry Brooks

This is very helpful. Including your own spreadsheet makes it easier to understand. I’m going to try it. Thanks for posting.

Thanks for your comment. I’m glad I could help. I’ve seen many descriptions of beat sheets, but few examples, so I thought I’d share mine.

Not at all surprised that you have a spreadsheet! Your planning is definitely an asset. Maybe I’m not as much of a pantser as I thought. I do have an Excel spreadsheet for one book (only wrote about half the scenes…idea was more interesting in theory than in practice). Anyway, it’s definitely a great way to get a feel for the structure of your book, particularly if you’re doing anything unusual.

Cyn: Thanks for commenting. I don’t think I’ll ever write another book without using a beat sheet from the beginning. Coupled with "the Snowflake Method," you can pretty well lay out your entire story before you even start writing.

One of the cool things about using a spreadsheet is that it is easy to extend. I recently added a "weather" column so I could make sure I didn’t have continuity errors in that regard. That became important in the scenes where I switch POV and have action that takes place simultaneously with previous or following scenes.

This is a great idea! I have written two technical books, and used a spreadsheet for my second one. I never even thought about using it for the fictional story I have started drafting.

Thanks for visiting, Greg. If you liked using a spreadsheet on your technical book, you’ll love it for your fiction too. The way it lets you instantly shift from the big picture view of your novel to the detailed scene view is priceless.

I’m a pantser and I have to admit I did a similar thing as I went on my current WIP. I didn’t user excel though, I downloaded Scrivener and created a template based on Larry’s downloadable beat sheet with the four part structure.

I put what my intention was for PP 1 at that point and started writing. I named each chapter/scene with the general idea of what happens as I went to be able to easily keep track of what was happening. When I hit PP 1, I then added what I wanted my Pinch Point to be at the pinch point section.

I used the note card function to track the other details (day, etc) as I went so that way I was being consistent. The end result probably has the same details. So, we pantsers don’t have to scream, if we just keep the basic structure in mind as we go.

Maybe using the template makes me only a half-way pantser, but I don’t know the whole story before I go just the first plot point/hook. Then I take off on how do I get there.

Anyway, great idea, it gives me an idea of what else to track as I go next time.

Thanks for visiting and commenting, Mel.

Your approach sounds suspiciously like plotting, but I’m sure the spectrum is broad between inveterate plotters on the one hand and inveterate pantsers on the other.

As organized and detailed as the final product may look, I didn’t sit down and figure all that out from the start. I started with only the main plot points, and I came up with the scenes I needed to get there as I wrote the novel.

Some writers prefer to have a full outline completed, with every scene plotted out at at least a high level, before they begin writing. I discovered that I get bored after a while when I’m working at that high of a level. I need to "put feet on the ground" at some point and let the characters tell me how they want to reach the main plot points.

I guess part of me is still a pantser; between plotting sessions that is! 😉

Now that anyone can self-publish, everyone and their mother claims to be a "Writer" LoL. One look at your "beat sheet" is proof enough of that (you don’t even title the necessary stages of plot let alone explain them, LoL). And before you respond (or, more likely, delete my comment as fast as possible so no one else happens to see it) PLEASE list the publishing house that you sold your original work to . . . EXACTLY. You, sir, are NOT a writer, and thus should stop 1. claiming to be, and 2. stop claiming you possess knowledge that would help other writers.

I approved the above comment because it demonstrates something that everyone who self publishes will have to deal with at some point or another: haters.

I have no idea who "You Suck" is because the coward refused to use his/her own name. That’s okay. This anonymous attempt to tear down my confidence and disparage my work means nothing to me.

If any of my fellow writers get drive-by, anonymous, and unsubstantiated messages of hate like this, please don’t let them bring you down. This isn’t about me. It isn’t about my work. It is about the fear, cruelty, and jealousy of someone who has tried to self publish and failed or who is threatened by the changes happening in the publishing world. There’s no other reason to bother leaving such a rude message.

We do not have to justify or explain ourselves to Mr. You Suck or anyone else. Our best revenge is to keep writing and keep publishing.